Breaking Bread with Natalie Jenkins

Sliced Bread Staff Writers Courtney Pine and Daniel Zhang Discuss Constructed Environments, Ghosts, and all things Rocks with Natalie Jenkins

Instagram: @nataliejankins Website: https://nataliejenkins.cargo.site

Sliced Bread (S.B.): Hi Natalie, thanks so much for coming. This is just to get to know you a bit as both a person and an artist to understand better where your inspiration comes from for some of your pieces. So, we were wondering what your creative process looks like.

Natalie Jenkins (N.J.): I guess my creative process is a lot of looking at things. I feel like, in the same way that you can't be a good musician unless you listen to a ton of music, the only way to learn art is to look at art. So, I just have to gather everything that I find interesting and print it out and pin it up on my walls or keep it all in a Google folder, and that's where I get my departure points for formal references or ideas that I want to convey. My main issue is that I want to make things that, if not directly stating what they're about or are interested in, I want them to at least hint at them or point at them. Because I think there's a lot of frustration about access to concepts in contemporary art within the broader public, so my starting impulse is to think about things that are accessible and relatable or interesting to a broader public.

“My goal is to make something that’s visually interesting or provokes an emotion in some way, because if you can make someone feel something or just interest them, then that’s the first step in communicating a concept. ”

S.B.: How do you aim to bridge the gap between really conceptual topics and the layman who doesn't understand them?

N.J.: I think it's hard. It's really hard because it's really easy to, as college students with our majors, just be really good at one thing or really have a lot of knowledge in one really niche area. You might have one specific video game that you know a lot about or a certain kind of movie that you're really interested in, but I feel like if you can make something that's visually interesting, that is the first step in bridging that gap of this kind of this academic talk that we see a lot in the curatorial wall labels, art texts, and broader public understanding. So, I would say my goal is to make something that's visually interesting or provokes an emotion in some way, because if you can make someone feel something or just interest them, then that's the first step in communicating a concept.

S.B.: I definitely think you succeed a lot in getting that visual interest with your work. I also noted that in your wider portfolio, you have both photography and sculpture, and intuitively, those sort of feel like distinct fields – is there any reason you chose to use both of those mediums and, is there any sort of intersection between the two?

N.J.: I'm trying to figure out how I can combine my photographic practice with my sculptural works, but, at the moment, my interest in photography is maybe less as an artistic medium and more as a means of collecting ideas or collecting images that are interesting to me. I think this is the same for a lot of people, because we all have phones in our cameras, and pictures are an act of collecting or an act of saving. So, I have pictures of every little bit and bop that I see out in the street or any moment with my friends. And I think that same kind of impulse of wanting to preserve a feeling or preserve a moment or preserve something interesting that I saw out in the street is where my photographic practice comes in. But, I'm still trying to work out the conversation between that and my sculptures.

S.B.: I’ve definitely noticed this use of mixing mediums, especially in the piece “homescroll.” So, I was wondering what role dimensionality plays in “homescroll,” and how the 2D and 3D combine.

Jenkins’ “homescroll”

N.J.: Yeah, so for that piece, I was specifically interested in portrayals of all the spaces I've inhabited during my life. So, it's like a very long piece of paper that I drew every single space I could remember in the last 21 years of my life on that piece, but only a small section of that is visible, and the rest is coiled up on the wall and on the ground where it's secured. That bit of knowing that there are images there, but they're resistant to being seen, kind of in that dimensionality of the length and the rolling, relates to how I experience time. Because even though in one sense it is linear, in a theoretical sense, in an experiential way, it's very non-linear, and there are things that really stand out in our memory. In our recent memory, there are things that we know are there. You're in this place, you experience something or something was important to you, but it's kind of tucked away, all the way in the recesses of your mind, so it's resistant to being seen or it's resistant to being accessed, even though you know, at one point, your body occupied that space.

S.B.: The environment clearly plays such a large role in your sculptural work—how would you say your art works in conversation with environmental preservation and topics like that?

“I’m interested in how I can represent or capture or reimagine the environment.”

N.J.: Yeah, that's a great question. So, my research focus, because I also study art history, is land art, and the more celebrated canonical land artists are a lot of these kinds of heroic Western male figures that made really large-scale land artworks that are somewhat environmentally destructive; and so even though there was a large body of female land artists working at that same period, the majority of the funding and the recognition was going to these male land artists who were blowing up holes or staining the desert or moving huge amounts of dirt, like tons and tons. So I feel like that is one way you could approach the landscape that comes from maybe a more colonial perspective or similar perspective, but there are other ways we can relate to or reimagine or capture the landscape, in a means that is less environmentally destructive, perhaps? Like, I think it's impossible to be a young person and not care about the environment, cause that's something that's so pressing for all of us. But, I'm interested in how I can represent or capture or reimagine the environment. And it contains sculpture in a way that is faithful to the feeling of the landscape, but is not harming the landscape.

S.B.: It seems to me that this sort of like colonial man, creating these built environments, seems to be very – almost antithetical to the natural environment, and your work itself also has a lot to deal with, like the interplays between the natural environment and I guess what we would call a constructed environment. So, do you think there's sort of antagonistic relationship or is there some sort of larger interplay going on? How does that inform your work?

N.J.: I definitely was interested in that with my major recent piece, [“the weight of being”]. That's the welded metal structure that has the rocks suspended. I was seeing all these videos of trucks trying to move with large rocks and collapsing, even though ancient methods of heavy transport were able to move these megaliths without seeing the destruction of their moving technologies. It made me think about how the landscape can resist or confirm certain incursions we might make or certain developments we might want to build, and this kind of futile act of trying to control the environment or trying to constrain and define the environment by a grid or by a city or by a road system. And I think I was trying to get at that with the strain of this rock that I snatched somewhere from in Chicago. I put it in this piece of polyvinyl and after like a month, it fell through the polyvinyl because it couldn't hold the weight of it any longer and it was just stretching and stretching and stretching for that one month because the rock was so heavy. So, I can make something that can hold this natural item for a certain amount of time, but it's going to give way eventually and it's kind of a futile act: that moment of trying to capture and keep it in this plastic structure before it eventually escapes again.

Jenkins’ “the weight of being”

S.B.: Do you still have most of your sculptural pieces around? Have you gotten to see how they've changed over time?

N.J.: I have a few around, and others I've ripped apart and taken for their materials, so that piece is one of them. I think the works that are sediment-related or incorporate some sort of dirt or sand–which is a couple of my works–do not hold up over time because the sediment is loose, it gets scattered, it falls around my studio, it falls around Logan. It doesn't hold form for very long because ultimately there's nothing really holding it in a piled shape other than gravity. So, any sort of movement or interruption to the sculpture will scatter all of the sediment. And that's also kind of a futile act of trying to scrape that all up and dump it back into my sculpture. So, I don't mind the erosion or the decay, to borrow natural terms. I feel like that's part of the natural lifespan. And using these kinds of materials, I think I'm not interested in making perfect objects that will live in a museum, be historicized, or be around forever. I think it's just interesting to assemble all these materials at one moment in time and then let them fall apart at another moment in time.

“I think I’m not interested in making perfect objects that will live in a museum, be historicized, or be around forever. I think it’s just interesting to assemble all these materials at one moment in time and then let them fall apart at another moment in time.”

S.B.: Like it's almost Sisyphean to try to control the natural.

N.J.: Exactly, yeah.

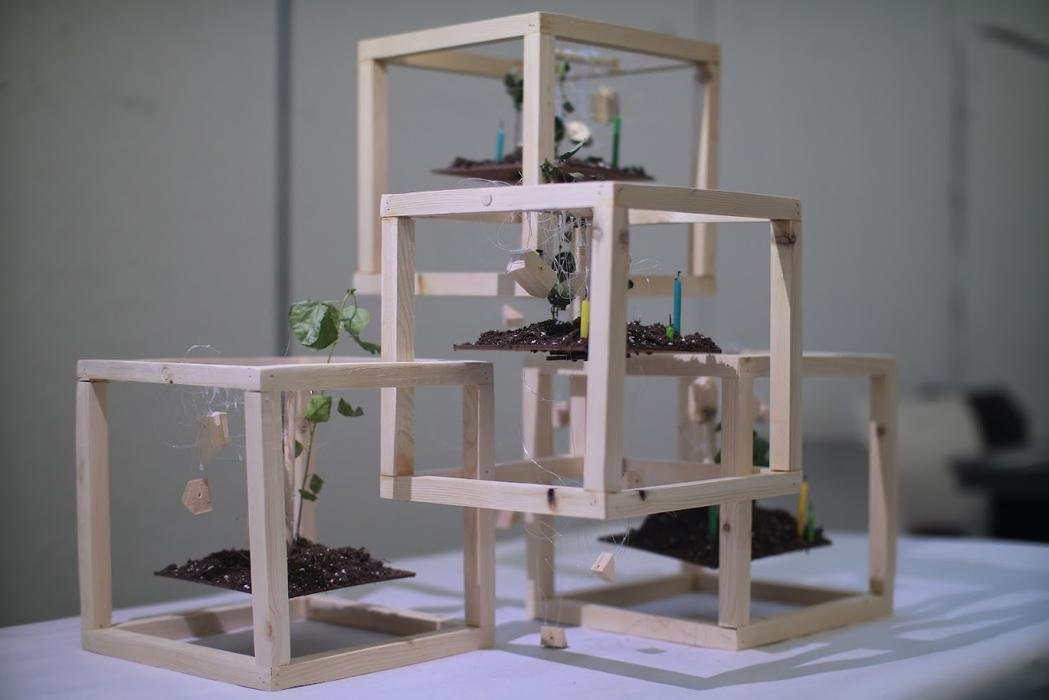

S.B.: I think that the work that stands out the most to me in terms of actually having that sort of organic element is the “container for life worlds.” What was your thinking behind that piece, especially behind the idea of containment, and how, if, and whether life should be contained in that way?

Jenkins’ “container for life worlds”

N.J.: Yeah. So I had–or I still have, I guess, a lot of pets growing up. My parents only ever wanted to have animals that can be contained in a terrarium or a cage. So I never had a dog or a cat, but I had lizards and a chinchilla and tarantulas and all sorts of wacky fish. And when you're a kid, that's really fun and exciting because it's like, “Oh, I just have this animal in my house and it's awesome.” But I also think about how we can possibly recreate a whole landscape in the confines of a terrarium or a zoo that perfectly replicates the environment in which this animal or this plant would actually live. Not to say I’m anti-pet, right! But, there are some species that would maybe get more at like a habitat that they would actually live in, like a fish, rather than like an elephant. There’s definitely a scale.

But on the whole, this idea of containment or control as it relates to the natural environment, I think is something that's a very human impulse, and also something that is necessitated by our existence. We have to control the environment, we have to grow crops for us to survive, we have to create shelters for us to live, but it's also a never-ending kind of quest, because as we create new solutions to increase the food supply or house more people, it also creates more problems about power, about ecological balance, and about natural resources that are finite. So yeah, I think this containment is not something that’s ever really possible, but it's also something that we will continue to engage with for the rest of our existence as humans. And so, I like that idea of containment and bringing in those natural materials into a sculpture that creates geometric boundaries of containment, but doesn't necessarily actually control those elements. And even when I was moving that sculpture around, I was dropping dirt everywhere. It was such a mess, so I’m proving my own point, I guess.

S.B.: Do you think that the theme of containment shows up in any of your other pieces or even in your photography?

N.J.: I definitely think so. I think photography, in and of itself, is containment. I think there are a lot of variables that you, as a photographer, control in the act of taking a photo, so it's not like you're reproducing or creating a faithful representation of something. There are all these factors that are under your control in a contained environment, and then you have this snapshot of this thing you created from what was and that's what exists as a file. And then, I think some of my other sculptures also are interested in containment–with “sailing stone,” I tried to recreate these stones that, until 20 years ago, we did not know why they moved around the desert. It was kind of a scientific mystery, and they’d create these paths as they carved through the sand. There was a lot of guessing it was aliens or guessing it was ghosts or someone coming and dragging all these rocks. So, I was interested in containing or capturing that kind of phenomenon and putting it into a sculpture. So, I tried to emulate that in that little platform, or again with the sculpture where I suspended the rock [“the weight of being”]. That's also interested in ideas of containment or control.

Jenkins’ “sailing stone”

S.B.: Another piece that I'd love to hear your thoughts on is “cybernetic staircase.” It's constructed out of a lot of these natural materials, but it definitely evokes this very man-made, constructed artifice. It has those [constructed] connotations, so I was wondering how those collide.

Jenkins’ “CYBERNETIC STAIRCASE”

N.J.: For that piece, I was interested in systems of construction as systems of control or as man-made constructions. I was interested in the systematic. I just repeated the same process over and over and continued building up that staircase until I could no longer get it out of the building. And then I stopped. But I liked that kind of repetitive structure, because it kind of implies a certain control or a certain pattern in how we develop structures in the built environment. And, I wanted there to be a reflection to kind of extend it even further. So, if you're standing and looking at it, the piece extends up, but it also extends downward, ad infinitum. So it's kind of this never-ending, repeating structure that's maybe citing some of our tactics regarding the built environment or construction and how we try to control or plan out human behavior through our built environment.

S.B.: How do you think this piece and some of your other pieces are impacted by materials you have available in terms of what gets to be made from wood as opposed to metal?

N.J.:That's a good question. I think a lot of the choices I make about material are purely just what I like to work with or what I like the touch and look of. So, I think that's where my own voice as an artist or my own impulse as an artist is consistent in my work, in that I am interested in a lot of these natural materials or materials that approximate natural materials. Like, even though steel, as it exists in my sculptures, is not a naturally occurring element, it's refined or derived from natural materials. And I don't know exactly what it is, but there's just something that I find interesting or that I keep returning to in wood or in dirt or in metal. Because I feel like they're so raw and they're so easily manipulated to kind of create things that reference themselves, but also live within that kind of world with the natural rather than like plastics or glass or paper–things that are farther removed from the world of the natural.

S.B.: I was really struck by your “mechanism for luring and capturing ghosts” and [the idea of] the supernatural. And I think that goes back to the idea of containment, but maybe even containment on a knowledge level, like if by classifying something, you could be getting rid of those other possibilities, or getting rid of the ghosts. And with that in mind, what are your thoughts on–well, ghosts?

“I think it’s really hard for me to accept that you and I are just meat and bones and electricity in our brains. I feel like there has to be some sort of energy or soul that extends beyond those constructions, the elements that make us up. And so, that energy has to go somewhere, and you see it in that piece.”

Jenkins’ “mechanism for luring and capturing ghosts”

N.J.: I think ghosts as the the pictures you've seen in movies or like popular culture are maybe a bit of a–well, not to get too controversial–but a bit of a Christian-manufactured idea. A lot of these ghost movies you see relate back to having to repent to God and then the ghost will stop bothering you or purgatory before going to heaven, allowing them to reach salvation. But I do think that beings are more than just the sum of their parts. Like, I think it's really hard for me to accept that you and I are just meat and bones and electricity in our brains. I feel like there has to be some sort of energy or soul that extends beyond those constructions, the elements that make us up. And so, that energy has to go somewhere, and you see it in that piece.

I put beef in a cup and I put it on the structure, because I was reading about how–and this might be vegan propaganda–but I was reading about how when you slaughter animals for consumption, animals that are in poor conditions on the farms, like on these factory farms, if they're under a lot of stress, the cortisol stress hormones that these animals have, the fear that they have at the moment they get slaughtered, is released into the meat. So there's like an energy of stress or an energy of fear that exists in the flesh after the life is extinguished, but the energy is still there. So, I don't think it's like a ghost as in transparent people; I think it's a ghost, as in traces of energy that get passed through the natural environment. And we don't necessarily have to understand it or describe it or label it as one particular spirit or religion or faith. That's also just a biological fact–like these trophic levels–and we're passing energy and there's kind of something intangible that's getting continued on.

S.B.: So, do you think that this mechanism is used to lure and capture the ghosts of cows?

N.J.: I don't know. I think that the emotion of fear and stress is so universal beyond just a cow or a livestock animal, that any sort of energy that is lost, that is wandering, would respond to such an intense signal of fear or signal of stress. I got that meat from a friend. I don't eat meat, but I got that meat from a friend who bought it and then wasn't gonna use it. But he got it from a big-box grocery store, Jewel-Osco. And so, they get their meat from these factory farms, right? And I understand we have industrialized to feed our populations, but also, there's definitely a certain amount of fear and stress that exists in that kind of honing signal that I sent out to whatever potential energies may be in the Hyde Park land area, and you don't have to be a cow or a human to feel fear. That's kind of universal. I think that's something people respond to–anything responds to. Everything feels fear.

S.B.: Yeah, and I imagine you can make the argument for a fear and stress of the environment overall, and like the haunting of the environment. Do you think that that sort of plays into this interaction between the environment, the natural landscape, and haunting in your art?

“My thinking about the environment as it relates to my art is foregrounded by a fear or an anxiety, and I think that also relates to the idea of control.”

N.J.: I definitely think it's a subconscious impulse for me. I think any considerations of the environment we have now are foregrounded by fear and foregrounded by anxiety, and it's kind of impossible for me to imagine an ecology without fear because all the news you read or all the media you consume is about how the last rhino just died, or there's a 1000 kakapos left in New Zealand, like all this terrible news regarding the environment and regarding the climate. And so, my thinking about the environment as it relates to my art is foregrounded by a fear or an anxiety, and I think that also relates to the idea of control. I'm someone who, if I am afraid of something, if I'm fearful or nervous or something, I feel like every aspect of it has to be in order to overcome that anxiety. And I think that also translates to a lot of the solutions we're trying to seek in the modern world regarding climate, regarding human populations, regarding scientific development. It's like all foregrounded by fear and the needs of control. So I think those kinds of emotions relate to each other.

S.B.: Do you view your art as pessimistic, optimistic, or realistic when it comes to the environment?

N.J.: That's a good question. I would say it's definitely not optimistic, but I also don't think it's pessimistic. I think in my work, I'm just trying to relate to the environment in a way that I can, and I think that what people draw out from what they're seeing speaks to how they relate to the environment.

And so, even though I have these ideas about climate and about ecology and about fear and climate change and these sorts of developments, I also think that the works just have an energy that relates to the environment that other people can pick up on and understand in their own way.

S.B.: I'd like to bring it to the last sculpture on your website, which is “rockfurniture,” and it seems like somewhat of a departure because of its lightheartedness. It's just fantastic with the googly eyes on the rocks sitting on their little wooden pieces of furniture, so I guess I'm just wondering, what inspired you to add that sort of levity to that sculpture?

Jenkins’ “rockfurniture”

N.J.: I think I realized that I was being too self-serious and also for a lot of the sculptures that I am undertaking, they're such big projects that once I start them, that's all I'm working on, and that just consumes me for weeks at a time. So, I just wanted to make something that was fun and exciting and that I could give to my friends, and they could just have a little bit of my impulse in their home spaces.

I thought about how I'm projecting a lot of this fear and anxiety onto my materials, but what if I wanted to like, care for them or give them energy–or build them furniture? So, I was like, “How would it be comfortable to sit If you were a rock?” And I don't think it would be comfortable to sit, but you could kind of be suspended in a pseudo-sit, and so that's what I did. I put them in the little frames and I gave them eyes because they’d probably want to see stuff while they're sitting and looking out at the world.

S.B.: Before we do the last question, I have just one more question–based on how we may have gotten a little out of order, my question is actually: can you tell us a bit more about your development as an artist and how you got started? And where are you trying to go in the future?

N.J.: Art is actually a relatively new thing for me–or I should say, visual art. I wasn't really engaged in visual art at all growing up. That wasn't really like an option for me, or it didn't feel like an option. And so, then I came to UChicago, and it was COVID and I was just filling my core and I took an Arts 101 class, “On Images,” and I was like, “This is fun.” I mean, it was remote, but I was having a good time. And then, I was like, “What if I major in this?” And then, I told my parents, and they were like, “No.” And then I did it anyway, but I had taken my first two years of college to fill my Core anyways, so really I've only been making a lot of stuff for, like, the last two years. And I tried painting and drawing, and everyone can draw, everyone can paint. I believe that some people are better than others, but everyone can really do that. And I'm one of those people who is not better than others, so that was a no-go for me.

I think the ideas I was interested in were better conveyed in the sculptural, like in the 3D, than in the two-dimensional. And I really loved the materiality of wood and metal and sculpture. So that really clicked with me, and I wanted to keep doing that. So I'm still pursuing sculpture, but I think, in the future, I'm interested in pushing my sculptures further and making my ideas more literal, communicating them even stronger. That's my forever battle: figuring out how to best communicate my feelings to people who look at the things that I make.

S.B.: Is there anything else that you'd like to add about who you are as an artist or how you think about art?

N.J.: I think that art should be for everyone and art is for everyone. Everyone at this school or in the world stands to benefit from making something, and so I'm really interested in trying to make things that communicate strongly with the public because I want that to be accessible. And so, I don't want people to be intimidated by a lot of the rhetoric we see about contemporary art that it's like, “Oh, it's all for rich people, tax cuts, and tax evasion.” It doesn't make any sense. I think you don't have to like everything, but art is for everyone, it's worth making something or finding things that you like.